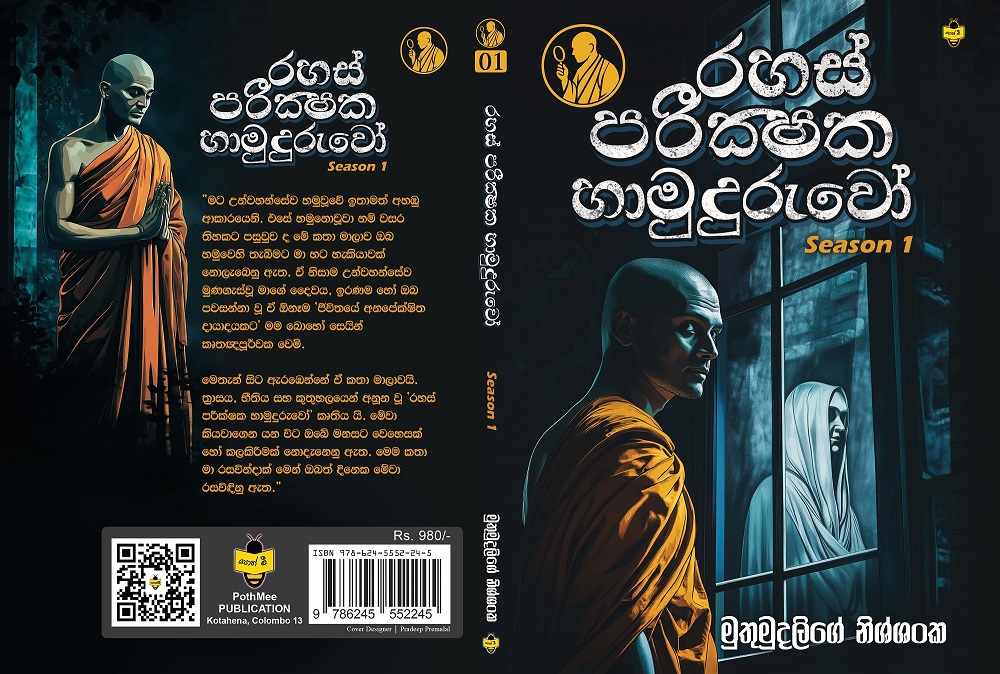

Preface to Rahas Parikshaka Hamuduruwo

What I write in this preface is yet another story. That is how every page of mine seems to turn—another tale, one after another. Perhaps it is because I love to tell stories. But unlike fiction, what I write here is truer than any crafted narrative. Therefore, I shall tell it in the same language with which I speak.

Matilda…

I first encountered Matilda in Yerevan Armenia, where she lived in a large apartment building. My wife Lucy and I lived on the fourth floor, while Matilda occupied the flat adjoining ours.

We intended to remain in that flat for at least a year, but it was not to be. Within seven months, Matilda drove us away.

She suffered from a mental disorder—simply put, she was insane. Every night she would shout, bang on doors, turn the lights on, and claim the building was on fire. She would scream that smoke was rising from below and that the fire brigade was on its way. Her madness, however, was not ordinary—it was of a strange kind.

In her mind, there was a whole drama of imagined stories which she believed as truth. One such tale was that the building beneath us was on fire.

So, day and night, she would cry:

“They’ve set fire downstairs! The fire brigade is coming! We can’t live here!”

At other times, she would hurl insults at the people below:

“Why are you setting fires down there? Are you trying to kill me too?”

To outsiders, her outbursts seemed absurd, even comic, but for those who lived beneath her, they were a source of deep torment.

At times, she would even dial 911, complaining about the “people below” setting fires. Police officers came several times, found nothing, and eventually left in anger. But Matilda’s ceaseless cries made even neighbors begin to wonder if some truth might lie in her claims.

Another obsession of hers was that “the people below are smoking drugs.” She would rant about it, claiming to smell strange fumes, which her mind twisted into a reality. Thus, her delusions became everyone’s burden.

One day, a parent from downstairs climbed up and scolded her harshly:

“Don’t speak such nonsense in front of our children!”

But we too had grown weary. With her constant clamor echoing through the walls, peace was impossible. After just four months, we left the flat—driven away by Matilda.

That was one story.

Later, the thought of Matilda’s madness came back to me when I visited the Barbican Library in London, where I had been invited to a program organized for the elderly by a social welfare association. Most participants were old men and women, some physically frail, some mentally affected. But despite their struggles, they were encouraged to write—poems, verses, little reflections.

I noticed something remarkable: though they had aged, though their bodies had weakened, they were all literate, all capable of writing something of meaning. Some poems were beautiful, deeply felt. One old man read a poem—yet strangely, his poem was about death.

It was in that moment Matilda’s story returned to me. What if someone, lost in delusion, mistook death itself for truth and wrote of it as real?

From there, the seed of Rahas Parikshaka Hamuduruwo took root: a weaving of Matilda’s delusions, an English poet’s melancholy verse, and true events I had once read of—an old woman peering each night through her binoculars and stumbling upon a real murder.

Thus, this book is not born of one tale, but from many—woven together into a single fabric.

Leave a Reply